Can Low-Protein Formulas Help Solve the Obesity Problem?

- Protein intakes of formula-fed infants are higher than those of breast-fed infants. Efforts to lower protein intakes of formula-fed infants are under way.

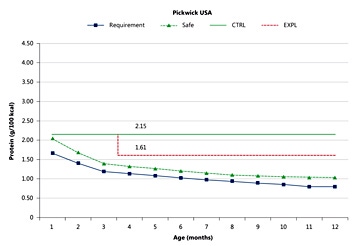

Protein requirements are defined as intakes that must on average be met in order to enable normal growth of the infant. Safe intakes are defined as requirements of those infants who have the highest needs [1]. As figure 1 illustrates, both requirements and safe intakes of normal infants decline markedly during the first 4–5 months of life. The protein content of breast milk (not shown) also declines during the first few months of lactation, resulting in the situation where protein intakes of breast-fed infants match the protein requirements of normal infants closely. As requirements and intakes of breast-fed infants are nearly identical, they are represented by the same symbol (blue) in figure 1. The fact that protein intakes of breast-fed infants follow requirements closely is important because it ensures there is neither a shortfall nor an excess of protein intake relative to protein requirement.

Protein intakes of infants fed formula follow a very different course. Since the protein content of formulas does not change with the age of the infant, as indicated in figure 1, protein intakes of formula-fed infants exceeds their protein requirements by an increasing margin. That is indicated in figure 1 by the green line representing the protein content of a typical formula. As the protein requirement of the infant continues to fall, the excess of protein becomes larger and larger. It has been documented in several localities [2] that protein intakes of older infants and toddlers typically exceed requirements for protein by a considerable margin. Since it is evident from epidemiological studies that excessively high protein intakes during infancy are associated with increased adiposity in childhood [3], the protein content of formulas fed to older infants has come under scrutiny. Importantly, in prospective studies, high protein intakes during infancy have been shown to lead to increased adiposity lasting into childhood [4, 5].

Lower-protein formulas have been developed in recent years as new dairy technologies have made it possible to improve the biological quality of formula protein. In a recently completed study [6], a formula with a low protein content of 1.61 g/100 kcal was compared to a standard formula with a protein content of 2.15 g/100 kcal (fig. 1). The study involved infants born to overweight and obese mothers They were enrolled in the feeding study at 3 months of age and fed the study formulas up to 1 year. Although infants in both formula groups showed what was considered normal growth, infants fed the low-protein formula grew significantly less rapidly than infants fed the high-protein formula. The growth-slowing effect of the lowprotein formula was particularly strong in infants of obese mothers and in infants who already were on a fast growth trajectory.

A similar study in infants of normal (as opposed to overweight) mothers showed a milder effect on growth after 3 months of a low-protein formula [7]. Importantly, however, it also showed that the low-protein formula supported normal growth, suggesting that the protein content of formulas could safely be reduced, thereby contributing to a reduction of overall high protein intakes in late infancy and bringing protein intakes closer to those of breast-fed infants. Now that the obesogenic potential of high protein intakes has been recognized, an overall reduction of intakes of protein appears desirable from an obesity prevention point of view. Reduction of the formula protein content offers a contribution to the fight to prevent obesity, in particular since low-protein formula represents an intervention at an age at which preventive efforts may be particularly effective.

- Dewey KG, Beaton G, Fjeld C, Lönnerdal B, Reeds P: Protein requirements of infants and children. Eur J Clin Nutr 1996;50:S119–S150.

- Alexy U, Kersting M, Sichert-Heller W, Manz F, Schöch G: Macronutrient intake of 3- to 36-month-old German infants and children: results of the DONALD study. Ann Nutr Metab 1999;43:14–22.

- Rolland-Cachera MF, Deheeger M, Akrout M, Bellisle F: Influence of macronutrients on adiposity development: a follow up study of nutrition and growth from 10 months to 8 years of age. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1995;19:573–578.

- Koletzko B, von Kries R, Closa R, Escribano J, Scaglioni S, Giovannini M, et al: Lower protein in infant formula is associated with lower weight up to age 2 y: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:1837– 1845.

- Weber M, Grote V, Closa-Monasterolo R, Escribano J, Langhendries J-P, Dain E, Giovannini M, et al: Lower protein content in infant formula reduces BMI and obesity risk at school age: follow-up of a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;99:1041–1051.

- Inostroza J, Haschke F, Steenhout P, Grathwohl D, Nelson SE, Ziegler EE: Low-protein formula slows weight gain in infants of overweight mothers. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014;59:70–77.

- Ziegler EE, Fields DA, Nelson SD, Chernausek SD, Steenhout P, Grathwohl D, Jeter JM, Nelson SE, Haschke F: Adequacy of infant formula with protein content of 1.6 g/100 kcal for infants between 3 and 12 months: A randomized multicenter trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, in press.